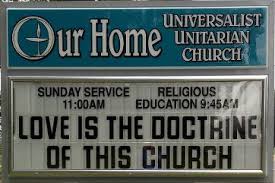

There is a new product on the theological market, Universalism, which advertises a new and improved deity, one much better than the old deity offered by such men as John Calvin, Jonathan Edwards—and John Chrysostom. The old deity could be wrathful, and would consign impenitent sinners to an eternal hell, an unquenchable fire. The new and improved deity is much nicer: he would never damn anyone eternally, and offers the good news that all will eventually be saved, no matter what their choices during their life. (One version of this deity declares that, well, it is true that not everyone will be saved, but at least no one will suffer eternally, for the non-saved will be incinerated into non-existence shortly after their resurrection and condemnation. This view shares with Universalism the conviction that a God of love would never damn anyone or allow them to suffer eternally.)

The new deity is marketed as a “more Christlike God”—meaning presumably more Christlike than the God proclaimed by the Church in the previous two millennia. This God, whether or not more Christlike, is certainly nicer and safer than the deity previously proclaimed. His only concern, seemingly, is love, which has eclipsed any concern for justice to the point of its effective obliteration. St. Paul would have us behold both the kindness and the severity of God—those who fell into apostasy who know His severity, but those who believed in Christ would know His kindness (Romans 11:22). In the new deity one finds only kindness. This Aslan is an emphatically tame lion.

I suspect this deity is popular with many in our generation because he bears a striking resemblance to ourselves. That is, this deity is tolerant, patient, loving, peaceable, accepting, all-embracing, all-forgiving, and emphatically non-judgmental—the very virtues at which our own generation excels and specializes. Wrath and vengeance against evil are foreign to his nature; he is not concerned with justice but only that his children enter into Paschal joy. He fits in well with our secular culture because, in fact, he is a creation of that culture. Universalism has remade the Biblical God into its own image. Naturally we find this God more congenial—we invented him and made him to look like ourselves.

But this deity bears little resemblance to the God of the Old Testament. That God was a man of war (Exodus 15:3), one who would wrap Himself in the garments of vengeance and go forth to wage war against the ungodly of the earth, staining His raiment in their justly-shed blood (Isaiah 59:17, 63:1-6). Though He did not desire the death of the wicked, but rather their repentance, He would mete out death to the wicked if they refused to repent (Ezekiel 33:11-13).

It is no good at this point invoking the long-exorcised spirit of Marcion, in an attempt to oppose the merciful deity of New Testament to the blood-thirsty one of Old Testament. All the pages of the Scriptures, both New Testament and Old, declare both the severity and the kindness of this God. Christ is no different than His Father, and Universalist attempts to be more Christlike than Christ can only do so by ignoring much of the New Testament picture of Jesus.

For the Universalists not only must discount the picture of God portrayed throughout the Old Testament, but must also discount much of the New Testament picture of our Lord as well. Christ is not only the one who welcomed and refused to condemn the penitent sinner (Luke 7:36f, John 8:2f), He is also the one who emphatically condemned the impenitent Pharisees. He called them sons of Gehenna, and said that the devil was their father, and that they could not hope to avoid the sentence of Gehenna themselves (Matthew 23:15, John 8:44, Matthew 23:33). The cities that rejected Him He condemned to be brought down into Hades, where they would find the fate of Sodom preferable to the one awaiting them on the day of judgment (Matthew 11:23-24). At the Second Coming He will deal out retribution in flaming fire to those who do not know God and who disobey the Gospel, as they pay the penalty of eternal destruction (2 Thessalonians 1:7-9). In His revelation to the seven churches of Asia He declared that He would wage war with the sword of His mouth against those who fell into worldliness, killing them with pestilence so that all the churches might know that He was the one who searched the minds and hearts, rewarding each one according to his deeds (Revelation 2:16, 23). It is unlikely that those who offer a more Christlike God are thinking of these parts of the New Testament picture of Christ. They prefer to excise such verses from their Bibles, and dwell only upon the verses which present Christ as the friend of sinners.

The Church throughout the ages has preserved in its picture of Christ the Scriptural balance between severity and kindness. It knows He is both the friend and advocate of penitent sinners who desires the salvation of all, and is also the just judge who metes out divine vengeance upon those who refuse to repent. Christ, like His Father, is both severe and kind, the one who opens heaven to the penitent sinner and condemns to hell the evil man who refuses repentance. The Church has always known this, Origen and his few Universalist friends notwithstanding. St. Paul knew it. St. John the Theologian knew it. St. John Chrysostom knew it. The Fathers of the Fifth Ecumenical Council knew it. Even Mr. Beaver, (in the Lewis classic, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) knew it. They knew that Christ our God is not a tame lion and that He is not safe. “Who said anything about safe? ‘Course He isn’t safe. But He’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.”