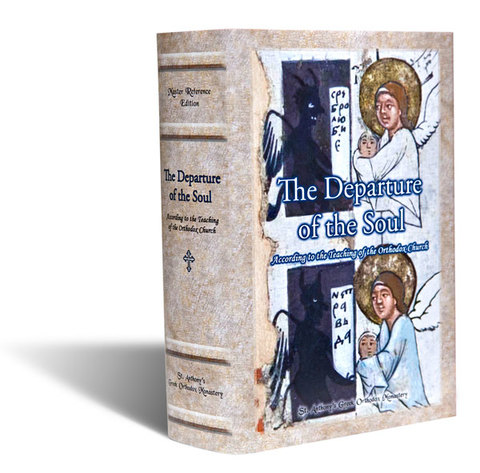

Lately a new book has become available, The Departure of the Soul, published by St. Anthony’s Greek Orthodox Monastery in Arizona. Its full title is, The Departure of the Soul According to the Teaching of the Orthodox Church; a Patristric anthology, and this about sums it up. It deals with the Scriptural material as interpreted by the Fathers, and goes on to examine the teaching as found in the liturgical services of the Orthodox Church, the writings of the saints, and the hagiography or lives of the saints. It contains an examination of the iconographic tradition expressing this teaching with an impressive 216 pages of full colour plates, and much more. It is a formidable volume, and not one to be held in one hand while drinking a Starbucks coffee with the other—it contains 1112 pages in all, bound sturdily between its two hard covers. That makes it a bargain at $58. It took five years to research and produce.

It also contains an impressive number of hierarchical introductory endorsements, including those of Metropolitan Joseph of the Antiochians, Metropolitan Hilarion of ROCOR, Bishop Mitrophan of the Serbian Church, Archbishop Nicolae of the Romanian Church, and my own archbishop Irenee of the OCA. (They will I trust forgive my lack of capitalization.) The volume concludes with a number of 17 academic endorsements from scholars writing to support the book, including the respected and prolific Archpriest John A. McGuckin. These impressed me even more than the hierarchical endorsements, if only because scholars are more vulnerable in their careers than are bishops, and must take greater care what they endorse. The fact that a number of scholars endorse the book is very significant, for works emanating from a monastic milieu do not always find a welcome reception in the world of Academia—or vice-versa.

The book was not written because the Athonite monks in Arizona had nothing else to do. In the Introduction it is explained that “In 1978, a lone author, Deacon Lev Puhalo (later Fr. Lazar Puhalo in tonsure), launched a campaign against the Orthodox Church’s 2,000-year old teaching on the trial of the soul at death”. His teaching was banned by his own jurisdiction (ROCOR) whose Synod warned that his writing “can cause great harm to the souls of the faithful”. Nevertheless (the Introduction continues) “Deacon Lev and several subsequent writers who reiterated his un-Orthodox views continued to issue their publications”. They note that these writings “have fuelled a controversy for nearly forty years, even to this present day”. Thus it was that in 2011 the editors of the book began their research into the topic. Their book represents the fruit of their extraordinary labour, including chapter 7, entitled “On the Falsifications, Misrepresentations, and Errors of Those Who Oppose the Teaching of the Orthodox Church”. Not surprisingly Puhalo comes in for detailed scrutiny, as editors present “over sixty fallacies which Puhalo used to attempt to support his invalid theories”, including many deliberate falsifications of both text and iconography. Puhalo’s personal history also comes in for some needed scrutiny in Appendix G, which narrates his “Extended Biographical Information”.

As a pastor, I note that even apart from the correction of distortions and misrepresentations of the Church’s Tradition, the book also serves as a corrective to the more widely-held errors of secular society, which routinely assumes that, with the possible exception of White Supremacists, terrorists, and Nazis, everyone goes to a heaven of some sort as soon as they die with little or no fuss. Look at the pages of Facebook or any social media as soon as any celebrity dies: there you will see a multitude of posts comforting themselves and others with the thought that the deceased celebrity has passed effortlessly through the Pearly Gates and is now strolling the streets of heaven (and possibly giving out autographs).

It reminds me of the old 1974 song by the Righteous Brothers, “Rock and Roll Heaven”. One of its lyrics reads, “If there’s a rock n’ roll heaven, well you know they’ve got a hell of a band…Jimmy gave us rainbows, and Janis took a piece of our hearts…There’s a spotlight waiting, no matter who you are, ‘cuz everybody’s got a song to sing, everyone’s a star”. A happy thought (and one that accords with today’s fascination with universalism), but is it sensible? The Jimmy who gave us rainbows was Jimi Hendrix, and the Janis who took a piece of our hearts was Janis Joplin. Jimi would become angry and violent when drunk or when he mixed alcohol with drugs. After his death in 1970 at the age of 27, an autopsy revealed that he choked to death on his own vomit while high on barbiturates. Janis, rarely seen without a bottle of her favourite “Southern Comfort”, died of accidental heroin overdose, possibly compounded by alcohol, in October 1970, also aged 27. One can and should have sympathy for such young people, but it is at least an open question whether they made it to heaven, despite their acknowledged skill in rock n’ roll. The point is this: our culture assumes that everyone makes it to heaven, especially celebrities. No fuss, no muss, no trial of the soul at the hour of death. Just a quick and painless step from choking to death here on your vomit to the heavenly spotlight there, “cuz everybody’s got a song to sing, everyone’s a star”. This is assumed without argument in our culture, and may not challenged at the office water-cooler without giving the impression of being a heartless, judgmental misanthrope. But the challenge to our culture needs badly to be made just the same. We may be grateful therefore that the monks in the Arizona desert have taken up that challenge, and done their work—and now offer it to us at such a comparatively low price. No church library should be without one.