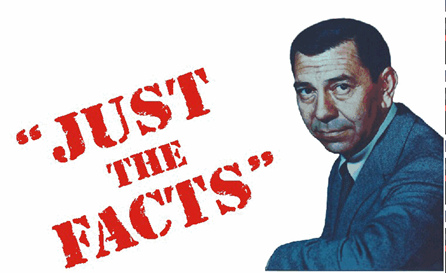

I cannot have been the only one to have noticed on Facebook and other public forums an overwhelming use of ad hominem arguments when discussing controversial topics. Whether the hot-button topic is abortion, the ordination of women, homosexuality, the revival of the office of deaconess, altar girls, transgender washrooms, Russia, the Ecumenical Patriarch, gun control, or the value of ecumenism, (to say nothing of American politics), things very quickly slide from the objective to the subjective. Rather than dealing with the actual substance of arguments by either disputing the facts or their interpretation, the respondents often respond by pointing out how heartless, misogynistic, arrogant, or generally terrible their opponent is. This may or may not be true, though it is difficult to see how someone could have such deep insight into the character of strangers, but even if true, it is irrelevant to the argument at hand. What matters is the reasonableness of the argument presented, not the general likability of the person presenting it. One sees this too in ad hominem attacks upon the scholarship involved: sources cited are derided as being too old or (among the Orthodox) too western, when presumably the only thing that really matters is whether or not what the cited source says is true. Unless the old source has said something which has later been proven by more recent scholarship to be unreliable, the date or provenance of the quote is as irrelevant as the likability of the person citing it. After wading through post after post of ad hominem responses online, one is tempted to reply with the quote often attributed to Sgt. Joe Friday from the television show Dragnet: “Just the facts, ma’am.”

The temptation to avoid dealing with the facts has a long and deep root in our culture. As early as 1941 C.S. Lewis examined the phenomenon in a slightly tongue-in-cheek essay entitled, ‘Bulverism’ or, The Foundation of 20th Century Thought. In it he wrote,

“The modern method is to assume without discussion that [one’s opponent] is wrong and then distract his attention from this by busily explaining how he became so silly. In the course of the last fifteen years I have found this vice so common that I have had to invent a name for it. I call it Bulverism. Some day I am going to write the biography of its imaginary inventor, Ezekiel Bulver, whose destiny was determined at the age of five when he heard his mother say to his father—who had been maintaining that two sides of a triangle were together greater than the third—‘Oh you say that because you are a man.’ ‘At that moment’, E. Bulver assures us, ‘there flashed across my opening mind the great truth that refutation is no necessary part of argument. Assume that your opponent is wrong and then explain his error and the world will be at your feet. Attempt to prove that he is wrong and the national dynamism of our age will thrust you to the wall.’”

Lewis was, of course, decrying the comparative absence of reason from popular argument in his day—an absence he detected throughout his culture in arguments about religion, economics, and politics. The Bulveristic approach is popular, then as now, because it is so easy to use—understanding, analyzing, and dissecting someone’s argument is hard work, especially if the argument is long and nuanced and argues for a position one finds personally repellent. Ignoring the argument and the facts and simply throwing verbal rocks is much easier. And it also pays greater immediate dividends, for people respond more quickly and more deeply to emotion than to reason. Painting one’s opponent in (for example) the glowing colours of a modernist apostate liberal—or perhaps the glowing colours of a fundamentalist fanatical zealot—are both easy enough to do, and very emotionally satisfying. Listening to their arguments with enough sympathy to try to understand how they might actually have a point somewhere is a lot more difficult. But if the issue under discussion is to begin to find resolution, this hard work must be undertaken. We must begin with just the facts, ma’am, just the facts.

I remember during a presentation at the weekend seminar “Marriage Encounter” how the presenter encouraged couples to hold hands while they argued. The idea was that the tactile connection of holding each other’s hands would keep the discussion from escalating out of control. I have never found it necessary to follow the advice in a domestic setting, but I still think it good advice in an ecclesiastical or even a political one. Not, of course, that one can actually hold the hands of the person one debates with online (or even see their faces). But we can hold hands metaphorically, and remember that the person with whom we may disagree is more than their online words—that he or she a person for whom Christ died, someone deeply loved by God. We owe it to them for God’s sake to listen as dispassionately as we can manage, and respond with calmness and charity. We don’t need ad hominem approaches. We can hold hands instead, and listen to the facts.