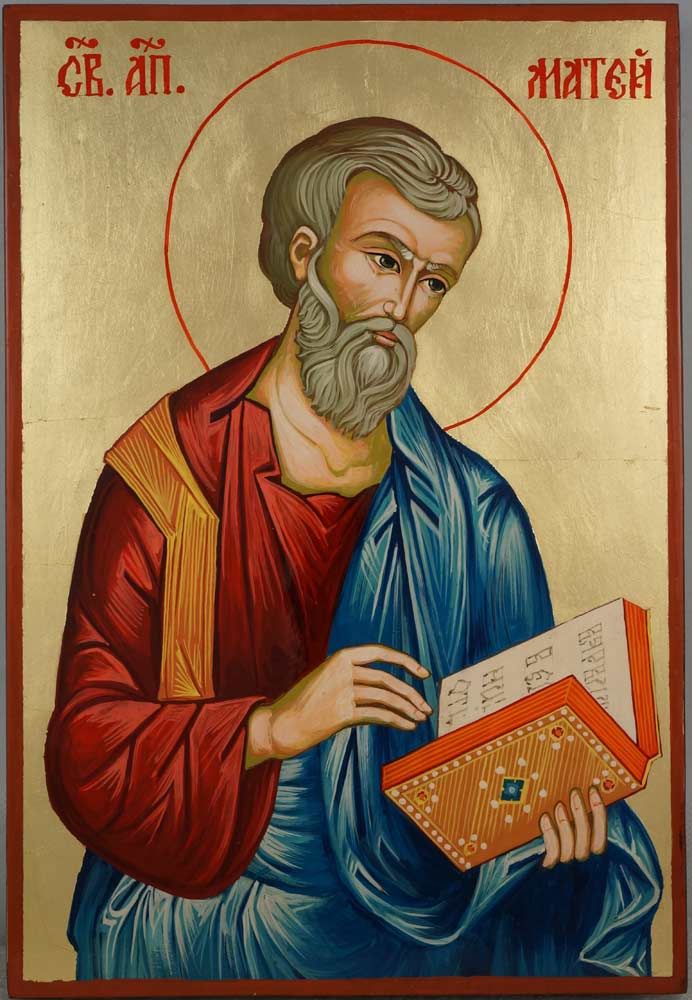

Today, as we begin to enter the Christmas and Theophany season, we begin a series on the use of the Old Testament in the early chapters of the Gospel of St. Matthew. We will examine his citations in his narrative of Christ’s birth, childhood and adulthood up to the time He settled in Capernaum, bringing a great light to the tribes of Zebulun and Naphtali and to all the world. St. Matthew (either the actual author of the Gospel or the one under whose blessing and authority it was first disseminated) took care to present Jesus as the fulfillment of the Hebrew Scriptures, the Old Testament, and by examining the use of the Old Testament in this Gospel we can see how deeply and creatively the Church used those Scriptures.

That apostolic use of the Old Testament differs in some ways from the hermeneutical methods of modern scholarship. Many modern scholars are solely concerned with the historical meaning of the text, and so are careful to locate the texts within their historical context. For such secular scholars, the historical meaning is the only one there is, and the deeper layers of meaning found by Christians like St. Matthew represent not a deeper layer of meaning intended by the Holy Spirit, but the importation of meanings foreign to it, an often ingenious but ultimately arbitrary eisegesis. Such scholars consider that the notion of the Scriptures being θεόπνευστος/ theopneustos, God-breathed, so that “men moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God” (2 Timothy 3:16, 2 Peter 1:21) as exegetically insupportable, and so do not delve into possible deeper meanings. Allegory becomes anathema, and typology a waste of scholarly time.

The historical Church, as represented by the Fathers, disagrees. It takes care to discover the historical context and to root its first exegesis there but, convinced that the Scriptures are not only human documents but also the Word of God, the Church delves further to uncover hidden meanings. St. Matthew’s Gospel is a prime example of such apostolic delving.

We begin by looking at the first Old Testament citation in that Gospel: that of Isaiah 7:14 in Matthew 1:23: “Behold, a virgin will be with child and bear a son, and they will call his name Emmanu-el which being translated means, ‘God is with us’”.

The text in Isaiah 7 is rooted in a crisis of its time in the 8th century B.C. The southern kingdom of Judah was under imminent threat of invasion from the north by a coalition between the northern kingdom of Israel and of Syria. The king of Judah, Ahaz, was going out to inspect the city’s defenses, including the water supply as he prepared for the coming siege. Like everyone else, Ahaz was terrified, and he had determined to trust in the great Assyrian empire for help and support—with all the religious compromises with a pagan land that such an alliance would entail.

For Isaiah such an alliance was out of the question. Instead of relying upon Assyria for help, Ahaz should instead rely upon Yahweh. The prophet therefore undertook to meet his king and convey a word of assurance from Yahweh that He would defend His people, and that Judah need not and should not make an alliance with Assyria. He even offered to perform a miracle to guarantee this. Isaiah invited Ahaz to name any sign or miracle he wanted, whether as deep as Sheol beneath or as high as heaven above The king, in a show of pretended piety that masked his secular determination to trust in political and military power rather than in God, refused the offer: “I will not ask, nor will I test Yahweh!” (Isaiah 7:11-12).

In response, Isaiah said, “Hear then, O house of David! Is it too little for you to weary men, that you weary my God also? Therefore the Lord Himself will give you a sign. Behold, an almah shall conceive and bear a son, and will call his name Emmanu-el. He will eat curds and honey when he knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good. For before the child knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good, the land before whose two kings you are in dread will be deserted (Isaiah 7:13-16).

Note that the essence of the sign consists in its timing, not in the manner of the birth. God declares that by the time that a son to be conceived and born to an almah (more on this word later) is old enough to know good-tasting food from bad, the land of the kings of Israel and Syria will be deserted and the threat from them will be over. The land of Judah will be humbled and left untilled and return to pasturage, so that the only food it provides will be that of curds and honey. This will be a sign that God is with His people, which is why women like the almah will name her son “Emmanu-el”.

We see an example of this naming being connected with current events in the following chapter. Isaiah is commanded to take witnesses and write plainly the words “Maher-shalal-hash-baz”, a name which means “swift spoil, speedy prey”. The witnesses would testify to the timing of the chosen name, and to the fact that the name was chosen before the threat was over. Isaiah then went in to his wife, and she conceived and bore a son, who was named “Maher-shalal-hash-baz”. The name of the child commemorated the events of those days, “for before the child knows how to cry ‘My father’ or ‘My mother,’ the wealth of Damascus and the spoil of Samaria [i.e. the riches of Syria and Israel] will be carried away before the king of Assyria” (Isaiah 8:4). This is, I suggest, given as an example of the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy to Ahaz in chapter 7. Mothers would name their children to celebrate and commemorate God’s deliverance of Judah from the threat of Syria and Israel, revealing that God was indeed with them.

What then of the almah mentioned in Isaiah 7:14, translated famously (or infamously) as “young woman” in the RSV and as παρθένος/ parthenos in the LXX? The Hebrew word means a young girl of marriageable age, and it is usually translated “virgin”, given the cultural fact that most such young girls of marriageable were in fact virginal at the time of their marriage (compare Genesis 24:43 where such an almah is sought for Isaac, and Song of Solomon 6:8, where the virginal almahs are listed along with the obviously non-virginal queens and concubines). It was thus natural for the LXX to translate almah as παρθένος, “virgin”. The emphasis though is upon the youth and marriageability of the girl, not on her anatomical virginity, though this was assumed.

We see then that the prophecy of Isaiah referred to events that would take place in his time and so could serve as an example to his king Ahaz. It could not, in its primary meaning, refer to the birth of Jesus centuries later, for this could not serve as a lesson to Ahaz. For Isaiah to have said to Ahaz “in seven hundred from now, when Jesus is born, the kings of Israel and Syria will be gone” would have made no sense and could hardly have served as the needed confirmation of Isaiah’s authority. Such an interpretation of Isaiah 7 also separates it from Isaiah 8, which was clearly intended to underscore it.

Why then did Matthew cite this as a prophecy of the virgin birth of Christ? The Jews had no such tradition or expectation that the Messiah would be miraculously born from a virgin, so that there was no need to interpret Isaiah 7 Christologically. Matthew did connect Christ’s birth with this Scripture because he knew that, unexpectedly, Jesus was born from a virgin, and this prophecy was a verbal confirmation of it.

The God who knew that His Son would be born of a virgin verbally tipped His hand (as it were) by hiding a reference to a later Christological miracle in a prophecy referring to another prior event. Matthew was not exegeting so much as digging, looking at a text he considered to be inspired and so replete with buried treasures.

Isaiah proclaimed to Israel that God was with His people (in Hebrew Emmanu-el) and that the proof was that an almah, παρθένος, virgin would conceive and give birth to a son. For Matthew, whose heart was lit up with the knowledge that God had indeed proven Himself to be with His people through His virgin-born Son, the text of Isaiah 7:14 was a startling verbal confirmation. The ancient words leaped off the prophetic page, revealing a Christological significance undreamt of by their original hearers.