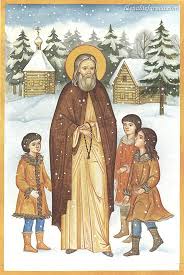

I have recently returned from a pilgrimage to Alaska, travelling aboard a (very non-ascetic) cruise ship, in the company of a number of other pilgrims led by Fr. Michael Oleksa and Fr. Laurent Cleenewerck, both of whom gave some talks to the group as we sailed north from Seattle. Fr. Michael gave the lion share of the talks, speaking to the group about the original Alaskan mission with his customary insight and enthusiasm, somehow pouring an entire lifetime of experience and scholarship into a few hours’ instruction. I had heard him speak on the Alaskan mission previously; he was as enthralling and wonderful as I remembered from before. The talks given by both priests made the shore leaves to Juneau and Sitka spiritually fruitful. Most of the other people aboard the cruise ship doubtless were there as tourists enjoying the ship’s excellent cuisine and Alaska’s natural beauty; we were there as pilgrims coming to venerate the holy places sanctified by the presence and labours of St. Herman, St. Juvenaly, St. Innocent, St. Jacob, and (as the Vespers stich for at the feast of All Saints of North America has it) of “the holy women, men, and children, those known to us and those known only to God”. It was a good week.

It came home to me again very forcefully how Orthodoxy began on this continent as a mission. People like St. Herman, St. Juvenaly, and St. Innocent were many hundreds of miles from their familiar homes; people like St. Jacob laboured long with a kind of Herculean effort spread over decades, enduring trials and undertaking feats that would have crushed most of us to the ground. What sustained them was their love for Christ and their zeal to bring His love to others who did not know Him. In other words, what sustained them was the missionary fire that burned in their hearts. It bears repeating: Orthodoxy began on this continent as a mission.

This bears repeating because so much of Orthodoxy in western eyes is not considered as missionary. It is considered as and is famous for lots of things: we are considered ancient, exotic, fascinating, mystical, and rich in symbolism. We are also mostly known for being Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, Serbian, Syrian, and Romanian, sometimes to the point where these adjectives melt with Orthodox identity and overwhelm it—we are “Greekorthodox” (one word), or “Russianorthodox” (one word), with the ethnic tag predominating. Or at least that is how we are often known. I remember being stopped at the Vancouver airport while wearing my cassock and looking very much like an Orthodox priest. “Are you Orthodox?” asked an inquirer. “Yes,” said I. “May I ask you a question?” “Sure.” “Where can I get some Greek food?” I was a bit surprised, and could only reply that finding a Greek restaurant in Vancouver should not be that difficult. For my inquirer, “Orthodox” meant “Greekorthodox”. I suspect that he was not that unusual.

We Orthodox are often happy to bear the dual label, and we sometimes trade upon it. We have food festivals (wonderful things in themselves), and turn this face to the world, displaying our culture with quite justifiable pride in terms of its cuisine, crafts, and dance. The possible down side of this display is that one might be tempted to define Orthodoxy mainly in terms of ethnic culture. In Canada anyway such a display garners more acceptance than a forthright missionary display of the Gospel. Our Prime Minister and our press (for example) happily hear about Greek dancing and our colourful Orthodox customs. They are happy to eat souvlaki as they shake hands and kiss babies at election time, and praise Greek Canadians for the richness of their religion. They are less happy to hear about Jesus Christ and His call to repent and believe, which is the real message of the Greek Orthodox Church and of every other Orthodox Church.

It is easy to enthuse about our rich and glorious cultural heritage, partly because there is so much of it. Our cultural heritage stretches back through the centuries, and came to its full flowering in Byzantium, which constituted a kind of high water mark for the Orthodox Church in terms of worldly influence. We had an emperor who presided over the ecumene—i.e. the Roman world—and our bishops were figures of grandeur and power. A few heretics and Jews aside, pretty much all the Roman world had been converted. If you count the Byzantine years generously from Constantine I in the early fourth century to Constantine XI in the mid-fifteenth century, the Orthodox time in the sun ran for over a thousand years. And if you add Slavic Orthodoxy into the mix, the period of ascendency runs for much longer (though admittedly rather further north of the original Byzantium). It is very heady stuff.

Perhaps that is why it is so hard to let it go and acknowledge that Byzantium now lies in the dust and the double-headed eagle no longer flies. We still insist on calling Istanbul “Constantinople” although no airline flies to Constantinople anymore. The planes all land in Istanbul. We still insist on calling the bishop residing in Istanbul “the Ecumenical Patriarch”, although the ecumene in which he once exercised his influence no longer exists. It is the same throughout the Orthodox world: the bishop of Antioch’s full title is “Patriarch of Antioch and All the East”, although “the East”—the original secular Roman diocese of “Oriens”—also no longer exists as a political division.

Here in the modern West our bishops are no longer figures of grandeur and power in society, despite the gorgeous Byzantine vestments they wear. Our display of Byzantine grandeur is tolerated by the secular world and its politicians and perhaps secretly smiled at a little. After all, we are so exotic and interesting. But we are also statistically insignificant and our voices carry no weight. Our bishops march courageously in the annual Right to Life March which numbers in the thousands. But in the West no one cares what we say, or whether or not we march. For all the pomp surviving the wreck of history, Byzantium is dead.

So, what is it that remains? Jesus Christ remains. He is the same yesterday, today, and forever. Kings may rise and fall, empires may come and go, but Christ and His Kingdom remain forever. And that means that our missionary mandate remains forever as well. After all, Byzantium only arose because Christians persevered in their missionary presentation of the Gospel through the years of persecution and blood.

That is why the example of Alaska is now so instructive and so necessary. The history of Orthodoxy in Alaska reminds us that the Church will always be missionary in its essence. As the times decree, our bishops may wear the honoured brocaded sakkos of Byzantium or the despised blood-stained garment of martyrdom, but their mission never changes. Led by them, the Church knows that it can never cease to be missionary. A day will come when we can lay our burden down and return the sword of the Spirit to its scabbard and cease our spiritual combat and tell the glorious story of our battle to the listening angels. But it is not this day. This day is the time for fighting, and preaching, and wielding the sword of the Spirit, and doing the work of mission. Our forefathers did this in Alaska. We in the West inherit from them this mantle and this mandate. Orthodoxy is missionary. We must tread the path of missionaries and saints.