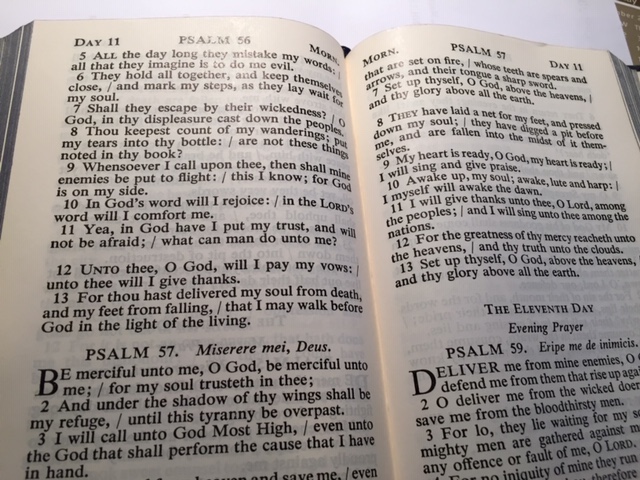

The 1962 edition of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer is very interesting. Along with the usual services of Morning and Evening Prayer and Holy Communion is a complete version of the Psalter. It is arranged for daily recitation at both Morning and Evening Prayer services so that the entire Psalter is recited liturgically every month. Well, more or less. For in the Prayerbook Psalter, right after Psalm 57 comes Psalm 59, prompting the obvious question, “Whatever happened to Psalm 58?” One is tempted to say that it vanished to keep the latter half of Psalm 137 company, for that also is missing.

It is not hard to imagine what prompted the decision to omit Psalm 58 and the latter half of Psalm 137 from the Psalter. They are famously violent. Psalm 58 constitutes an extended imprecation upon the wicked, and asks God to “break the teeth in their mouths; tear out the fangs of the young lions, O Lord! Let them be like the snail which dissolves into slime, like the untimely birth that never sees the sun…The righteous will rejoice when he sees the vengeance; he will bathe his feet in the blood of the wicked. Men will say, ‘Surely there is a reward for the righteous; surely there is a God who judges on earth!” The latter half of Psalm 137 reads, “Remember, O Lord, against the Edomites the day of Jerusalem, how they said, ‘Rase it, rase it! Down to its foundations!’ O daughter of Babylon, you devastator! Happy shall he be who requites you with what you have done to us! Happy shall he be who takes your little ones and dashes them against the rock!” It appears that the editors of the 1962 Prayerbook thought that these psalms were too violent to be suitable for congregational recitation, and so they simply excised them from the Prayerbook Psalter.

One understands the decision somewhat, for not everything in Holy Scripture is necessarily equally fit for all audiences. Certain passages in the Song of Solomon, for example, are more suitable for adults than for children (and yes, this is an invitation to look through the Song of Solomon to find the passages for yourself—or to buy a commentary on it). And reading aloud in church David’s speech threatening harm to Nabal and his house in 1 Samuel 25 is all but certain to provoke adolescent giggles when David says, “God do so to David and more also if by morning I leave any who piss against the wall of all who belong to him” (v. 22, usually bowdlerized as “leave so much as one male”). I understand the pastoral concern. But excising these bits of the Psalter runs the risk of giving the impression that these psalms are not just indelicate, but morally deficient.

Certainly C. S. Lewis thought so. In his otherwise wonderful Reflections on the Psalms, he interprets the many imprecations in the Psalter as unfortunate moral lapses on the part of the psalmist. In his chapter on “The Cursings” he describes the imprecations as expressions of “bitter personal vindictiveness”, as “hideously distorted”, and even as “devilish”. And Lewis here has many companions, men who quite happily excise from the Scriptures whatever they find uncongenial, attributing the parts they like to divine inspiration and the parts they object to as the regrettable result of God having to use a fallible human instrument.

But this will hardly do. If all Scripture is indeed “God-breathed” (2 Timothy 3:16) so that the one who relaxes one of the least of its commandments and teaches men so will be called least in the Kingdom of heaven (Matthew 5:19), then we cannot take the easy way out and divide the Scriptures into two categories, the Authoritative and the Embarrassing. Our Lord and His apostles teach us that we are stuck with the whole thing.

What then are we to make of the imprecations in the Psalter? Two things.

First of all we must recognize that the imprecations are not motivated simply by personal anguish and frustration. The psalmist is not vexed only by the injustice and oppression he is experiencing, but by the fact that the wicked oppress all the humble and vulnerable of the earth. He is not praying so much for personal vindication as for vindication for all the helpless poor, for all the victims of rapacity and rape, for all fatherless orphans whom the wicked swallow up with apparent impunity (e.g. Psalm 9:18, 10:18). He is, in fact, praying for the coming Kingdom of God, the day when Yahweh will judge all the world with righteousness and vindicate those who have hoped in Him (Psalm 98:8-9).

This prayer that God will one day come and judge the world, consuming sinners from the earth (Psalm 104:35) is not an unworthy or unchristian prayer. St. Paul calls this coming “our blessed hope” (Titus 2:13), and affirms that in that day Christ will come with His mighty angels in flaming fire, inflicting vengeance upon those who do not know God and who disobey the Gospel of our Lord Jesus (2 Thessalonians 1:7-8). The prayers of the psalmist and the sighing of the helpless poor who are crushed under the boot of the grinning wicked will not forever go unanswered. The imprecations in the Psalter are not the devilish expressions of bitter men, but the hope of all who have gone down before their oppressors still trusting in God.

Secondly, we read the psalms with a keener eye, digging into those ancient texts to find deeper meanings. In short, we also read them typologically and allegorically. For example, when the psalmist declared that God dwelt in Zion, he originally referred to God’s earthly Temple in the city of Jerusalem, which was in the time of David only about eleven acres in total size. But a deeper reading will recognize in the earthly real estate an image of the celestial abode of God, the heavenly Zion (Galatians 5: 26, Hebrews 12:22). In the same way, Israel’s national and earthly enemies (e.g. the Edomites) are images our spiritual enemies, the demons (and perhaps, by extension, of those controlled by the demonic). The psalmist’s prayers for victory over his enemies and his inculcation of “perfect hatred” against them (e.g. Psalm 139:22) find fulfillment in our own implacable hatred of sin and our ceaseless warfare against Satan. The psalter, like all the Old Testament, can be read on two levels: the original historical meaning and a deeper mystical meaning. And both readings contain treasures for our souls.

We are invited by our Tradition, therefore, to transpose the Psalter into this more profound key, and when we do, we find that the imprecations against our enemies form an important part of our spiritual life and our inner warfare against the enemies that constantly besiege us. Maybe the editors of the 1962 Prayerbook should have left Psalm 58 where it was after all.