I remember once hearing a light-hearted and self-deprecating bit of comedy from a country music station, in which the person repeatedly said, “You might be a red-neck if…” followed by a series of scenarios. For example, “You might be a red-neck if you cut your grass and find your truck”. “You might be a red-neck if you to go to family reunions to meet women”. “You might be a red-neck if you use a fishing licence as a form of ID”. It was all very funny, and very silly.

It also made me think recently in a similar vein that you might be a fundamentalist if… Listing the signs of fundamentalism might be a helpful exercise, for fundamentalists often are reluctant to recognize that they are fundamentalists.

One can perhaps understand why. The term “fundamentalist” is now sometimes used simply as a term of abuse. It originally described a group of Protestant theologians in the early twentieth century who authored a series of articles in books called The Fundamentals. These theologians were by no intellectual lightweights, but included men such as James Orr, B. B. Warfield, Bishop Ryle, and Dyson Hague. They were concerned to combat the spread of a destructive theological liberalism within Protestantism and wanted to offer a thoughtful and scholarly refutation.

The term, however, is now used almost exclusively pejoratively, and with little memory of its original use. It is currently reserved for people who hold unswervingly to their theological or ideological views in stubborn defiance of all facts and arguments, and who counter any evidence that argues contrary to their position simply by rejecting it out of hand because it does run counter to their entrenched position.

That is doubtless why no one likes to be called a fundamentalist—everyone would like to imagine that reason is on their side and that their faith can be rationally held and effectively defended. Whether or not it can be rationally held and effectively defended can only be determined by conducting a sustained calm and civil argument about it—which, unfortunately, is becoming rarer and rarer. In this Facebook world, it is far easier to simply write off those who disagree with us by fastening a label on them than it is to argue at length.

Perhaps this is why the label “fundamentalist” is so easy to use. In certain theological circles (you know who you are) the term serves to discredit one’s more conservative opponents without having to go to the trouble of finding out what they actually believe and arguing against it. In these liberal circles, a fundamentalist is defined as “anyone more theologically conservative than I am whom I find irritating, but am too lazy to engage and refute”. One notes in such cases that fundamentalism is a disease that afflicts liberals as well as conservatives. It is not a characteristic of any one theological camp so much as it is a symptom of an inner malady that can afflict anyone.

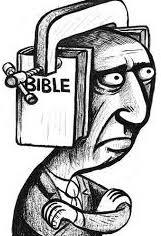

The fundamentalism with which I have come into intimate contact seems to be built upon a foundation of fear. It conceives of the Church as a fortress, a castle surrounded by a moat with its drawbridge pulled up, a bastion in which the faithful and pure remnant may take refuge from the complexities of the world. Whether it quotes the King James Bible With the Words of Christ in Red, or the Fathers of the Church, or the Catholic Magisterium, it uses its sources as a bulwark to keep nuance and doubtfulness at bay. Though there is indeed such a thing as a slippery slope, fundamentalists see it everywhere. Every challenge to their entrenched status quo is regarded as a slippery slope, and so for them the only safe course of action is to refuse the possibility of rethinking anything. For in their mind, if one piece is taken from the structure, everything will fall apart. Such is not the case when a structure is soundly and securely built. It is, however, the case when one deals with a house of cards, and so the fundamentalist fears to give ground on anything.

For example, if one admits that perhaps the Textus Receptus of the Bible does not represent the best manuscript tradition and that therefore 1 John 5:7 should be removed from the authentic text of that epistle, then fatal doubt must attend every other verse of the Bible. Because everything is of supreme importance, no change at all can be allowed in anything. For a fundamentalist, everything in his belief system therefore is of ultimate importance. There can be no small or insignificant doctrines or practices.

So, what are the characteristics of fundamentalism? I offer the following three characteristics of fundamentalists.

First of all, fundamentalists cling to conclusions held by their group and do not base their conclusions on the evidence or arguments which support them. In other words, their conclusions are not the fruit of interaction with evidence, but are predetermined apart from the evidence.

Secondly and as a result of this, evidence or arguments which do not support their predetermined conclusions are never refuted, but simply set aside. Fundamentalists consider that citing someone who supports their group’s predetermined conclusion is a sufficient answer and rebuttal of the evidence against them, which evidence is never meaningfully engaged.

Thirdly and also arising from the preceding, there is often a suspicion of modern scholarship and a reluctance to engage with it, since contrary evidence often arises from such scholarship. The work of scholars is rarely engaged or refuted, but simply written off as mere “rationalism”.

In the spirit of the country music monologue with which this blog piece began, I suggest that if these three things describe you, you might be a fundamentalist.

But after all, one might ask, “Why exactly is fundamentalism so wrong? In a world where so much unbelief reigns, and when people are so often swayed by the latest secular propaganda, is it so bad for someone to cling stubbornly to belief in the teeth of contrary evidence?” I would reply, “Yes, it is bad”, and for the following reasons.

First of all, a fundamentalist refusal to consider evidence makes it all but impossible for error to be corrected. Humility demands that we be willing to be corrected in the places where we are mistaken, but a refusal to countenance the possibility that we might need correcting makes the error invincible. It is the intellectual equivalent of hardening the heart. God wants us to grow and deepen in our understanding, and all growth involves at least some change. An unwillingness to listen to other voices cuts us off from the possibility of such growth.

Secondly, some fundamentalist errors weaken and impair our credibility in the eyes of the world which we hope to convert. The Church once reacted with fundamentalist defensiveness in its condemnation of Galileo, and even now we have not quite lived it down. Excluding growth in knowledge because it may force us to change some of our beliefs comes at a high cost. The Church had to step down from its fundamentalist zeal in the case of Galileo. And it found, somewhat to its surprise after it did, that the truths of its faith remained quite unchanged. We dare not reject things simply because we find them threatening. The world will rightly hold us up to contempt if we do.

Ultimately fundamentalism represents a closing of the mind and a narrowing of one’s world. Fundamentalism is driven by fear, and is ultimately incompatible with the Christian Faith, for God has not given us a spirit of fear, but of power, and love, and sound mind (2 Timothy 1:7). And anyway, why should we fear? Jesus is the truth, and He is in our midst.