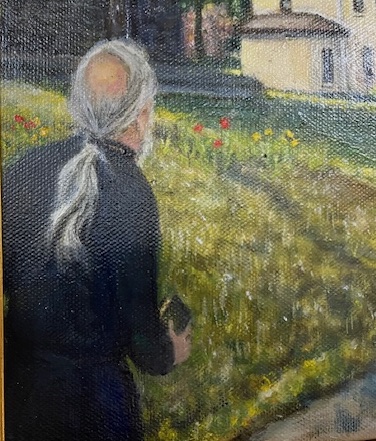

Recently a minor fracas in the narthex of our church was caused by (I kid you not) my long hair (see inset for a rear view of said hair). Since my hair steadfastly refuses to grow on the top of my head, you would think I could be cut a little slack for the bit that grows at the back, but apparently not.

Admittedly the problem was not with my hair alone, but also with our prayers to Mary, the use of the title of “Father” for clergy, the presence of icons in the church, and (lest any weirdness be lacking) by the fact that we served a weekly lunch in the church hall after Sunday Liturgy. The fracas was caused by two young men who began challenging our friendly narthex greeters immediately upon entering, loudly and aggressively stating their objections, pointing fingers, and generally threatening disruption. Happily the two young men decided not to enter the nave for the service after all, and stomped off shortly after entering. The doors, the doors!

Here I would like to address one of their objections, which due to its oddness is not often addressed by Orthodox apologists—that of long hair on men and especially on the clergy. It is true, as the two young men loudly stated, that St. Paul did write that “if a man has long hair it is a dishonour to him” (1 Corinthians 11:14 NASB). But, as my good wife used to remind me when she was a Baptist, “a text without a context is a pretext” and so we must examine the context in detail. When we do, we immediately see that Paul’s main point is not about a man’s hair, but about a woman’s veil.

In the Christian faith women found a dignity not often found in the religions and culture of their day. As far as salvation was concerned, in Christ there was no male and female, and men were instructed to grant honour to their wives as to their fellow-heirs of salvation lest their prayers be hindered (Galatians 3:8, 1 Peter 3:7). Women’s dignity was especially significant in Christianity when compared to her place in Judaism: in Judaism the sign of entry into the covenant (i.e. circumcision) was given to men alone, but in the Church the sign of entry (i.e. baptism) was equally given to men and women.

It was perhaps because of this exciting and new-found spiritual equality that some women in Corinth drew the conclusion that hierarchy in Christian marriage had been abolished, and that the wife need no longer submit to her husband and follow his leadership. In that culture, one sign of such submission was the veil—i.e. covering the head when out in public, such as in the marketplace or in church assembly. Some of the women therefore proudly dispensed with the veil, much to the chagrin of some (such as their husbands) and to the scandal of others in their Greco-Roman culture. In that culture, prostitutes went about with uncovered heads, but respectable married women did not. Paul heard about this and wrote them to correct it.

His first and most important point was that hierarchy still existed in Christian marriage. The world was hierarchically-constructed. Everyone had a head—every man had Christ as his head, just as Christ had God the Father as His head. And the wife had her husband as her head, despite the spiritual equality existing between them.

This submission in marriage was culturally-expressed: in church men must pray or prophesy bare-headed, while women must pray or prophesy with their head covered—i.e. dressing and comporting themselves as those in proper submission to their husbands. Part of Paul’s argument was from nature (Greek φύσις/ phusis), in this case meaning social convention, “the ways things are spozed to be” culturally). Here he is referring to the difference seen in men’s and women’s hair. A woman’s long hair was her glory—in that culture, a part of her sexual attractiveness, which is why respectable women covered their hair in public.

A woman displaying her long hair then was like a woman in a skimpy bathing suit today. And the point of long hair was not simply its length, but also how it was adorned. Despite the strictures about uncovered hair, upper class women indeed spent much time and money to adorn their hair so that it could be seen. Paul rebukes them for such concerns: “I want women to adorn themselves with proper clothing, modestly and discreetly, not with braided hair and gold or pearls or costly garments” (1 Timothy 2:9). Women’s long hair (especially rich women’s hair) was adorned with lace, ribbons, gold, and pearls. It was what we would call not just “hair”, but a “hairdo”—Greek κόμη/ kome, a different word than the normal Greek word for hair, which is τρίχες/ triches.

Here we find the main difference between the men and women’s hair. The issue was not simply length, but feminine adornment. It was considered dishonourable and effeminate for a man to have a hairdo (Greek κόμη, the word Paul uses in 1 Corinthians 11:14) and to adorn his hair in the same way as women adorned theirs.

Such an understanding of the difference between κόμη and τρίχες saves one from the subjective quagmire of determining just how long is long. The early Beatles were once considered to have “long hair”, though it was in fact shorter than most men’s hair in the Middle Ages. Each age has its own cultural standards regarding hair length and modesty and sacralizing one’s own time can lead to anachronistic absurdities. Does anything longer than the all-American 1950s crewcut for males count as feminized “long hair”? Did Marilyn Monroe have masculine short hair because it did not descend below her shoulders?

In short, what Paul was decrying was the use of feminine hairdos by men, the follicular equivalent of transvestitism. Long hair (such as worn by George Harrison in 1974 or by modern Orthodox clergy today) was not on St. Paul’s cultural radar.