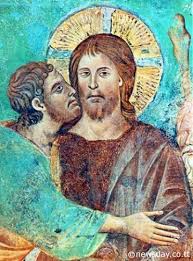

he hymns of Holy Week travel straight like arrows to the heart. There we learn of the harlot’s gratitude to Christ, she who formerly lived in the dark and moonless love of sin. We learn of the one who laboured long to serve the Master and increase the talents given to him and who was finally summoned to enter into the joy of his Lord. And also we learn of the apostasy of Judas. Judas remains in our liturgical tradition like a shadow, haunting the light. His fall warns us of the perennial danger of falling, and each time we approach the Chalice we speak his name and tremble: “I will not give You a kiss as did Judas, but like the thief will I confess You, remember me, O Lord, in Your Kingdom”.

The apostasy of Judas, like all acts of sin, presents the mind with a mystery. Why did he do it? How could he do it? The betrayal is perverse, impenetrable. The New Testament give the barest hints of his heart’s motivation. It describes him as a traitor, a devil, a thief who pilfered from the money-box entrusted to him. But even this does not go very far in resolving the mystery. Surely it cannot simply have been about money? The Twelve imagined that they were on the brink of entering a new world order with themselves as the new rulers. Surely in this new political order, money would not be a problem? Was the heart of Judas already growing cold while he served in his Lord? Did doubt and double-mindedness seep in, damaging and eroding integrity, drawing him ever more to side with the Lord’s foes? Did the money he pilfered end up in the hands of the Zealots? We can never know. The shadow that shrouded his heart remains, and prevents us from seeing into it very far.

But apostasy remains a possibility for everyone, and if one of the Twelve could fall, then no one can consider themselves immune and safe from temptation. I think of this when I sometimes peruse my Church Metrical Book, the record containing the names of all those in the last thirty years whom I baptized and chrismated. Many, happily enough, remain in the Church. But others have fallen away, and the joy which shone from the faces in the baptismal font did not serve to protect from subsequent apostasy. It is another arrow in the heart.

Some church leaders, knowing this, have taken steps to try to prevent it. One Greek bishop, realizing that many Greek teens no longer attend Church, wrote to his people and suggested that the problem was insufficient Hellenization, and that if the parents just used more Greek around the home, all would be well, and fewer of these young people would leave the Church. With respect, I suggest that identifying the Faith with one’s ethnic heritage is part of the problem, not part of the solution. The answer is not greater attention to ourselves and our background. The answer is greater attention to Jesus.

Parents need to help their children see the Lord, to have a living relationship with Him. It is not enough to know about Jesus, in the same way as one might know about the Battle of Hastings or other historical facts. They need also to know Jesus personally. Sadly this is still no guarantee that they will not subsequently choose poorly and abandon their Lord. But it is the best defence.

In this matter of seeing and knowing Jesus, I am reminded of a scene from C.S. Lewis’ final volume in his Narnian Chronicles, The Last Battle. In that world, there were two rival deities, Aslan and Tash, corresponding to our own Christ and Allah. A devout worshipper of Tash by the name of Emeth who had been taught from his boyhood to hate the name of Aslan, finally finds himself through a door into the other world. He beholds the bright sky and the wide lands and smells the sweetness, and thinks that he has surely come into the country of Tash. Then, bounding towards him with the speed of an ostrich and the size of an elephant, comes Aslan, the great Lion. “His hair was like pure gold and the brightness of his eyes like gold that was liquid in the furnace. He was more terrible than a flaming mountain, and his beauty surpassed all that was in the world even as a rose in bloom surpassed the dust of the desert.” “Then”, he said, “I fell at his feet and thought, Surely this is the hour of death, for the Lion (who is worthy of all honour) will know that I have served Tash all my days and not him. Nevertheless, it is better to see the Lion and die than to be king of the world and live and not to have seen him”.

This is the voice of authentic discipleship, the song of the Church, the confession of everyone who has known Jesus. The beauty of Jesus surpasses all that is in the world even as a rose in bloom surpasses the dust of the desert. It is better to see Him and die a martyr’s death than to be king of the world and live long in splendour and wealth, and not to have seen Him.

How can one see the great Lion and then abandon Him? How can anyone look long into those eyes of fire, and then turn away from His face and pursue other paths? It remains possible, though the darkness of perversity shrouds such a choice and makes it impenetrable to pious reason. But seeing the great Lion and knowing Him remains our best defense against the fate the Judas. That should be our goal in raising our children, and our own continued goal as well. The hymns of Holy Week warn us of the terrible possibility of apostasy. Let us tremble, and look to the Lion.