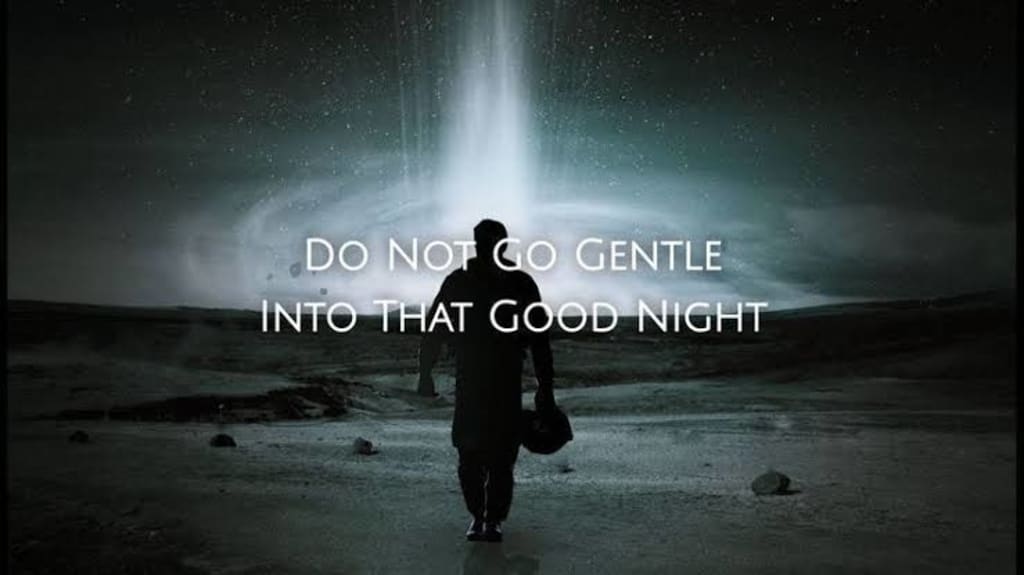

When I was young, I read a famous poem that I now regard as one of the strangest poems ever written. It is the one entitled “Do not go gentle into that good night” by Dylan Thomas with its repeated refrain “do not go gentle into that good night…rage, rage against the dying of the light”.

It was, in fact, a heartfelt cry of grief in the face of death, a rebel protest against our common mortality. The poet recognized death as an enemy, as an intolerable negation of all meaning and he called as witnesses wise men, good men, wild men, grave men and even his own father—all who would join him in his futile protest against the invincible onslaught of death. Death was the close of life’s day, the good night after the setting of a long sun.

The poet railed against docile philosophers, those who faced their death with resigned compliance. Away with such gentleness! Away with those who would meekly obey the summons to die and allow themselves to be herded unprotesting into Nazi cattle-cars bound for deathcamps! Away with those who would go gentle into the good night of death! Death may indeed conquer and claim all, but let it not find us timidly submissive, quietly lying down before the final blow. Let it find us raving and burning in splendid defiance, raging, raging against the dying of the light.

Such was Dylan Thomas’ glorious affirmation of the goodness of life, his Battle Hymn of the Republic against death’s inevitable victory. Dylan delighted in the light of day, in the bright frail deeds of good men done under the sun, in wild men who caught and sung the sun in flight, of grave men with eyes that blazed like gay meteors. For him death was nothing but darkness, the end of all light and wildness and joy. No wonder he burned and raged against its ending.

And that is why I now find his poem so odd and strange for I have come to see that this life, for all its glory and its frail bright deeds, is lived in a land of shadow. Dylan justly and beautifully sang of life’s splendors. But life contains more than those splendors. It also contains darkness and heartbreak. The human heart has lashed out against God and filled His world with war and crime, with sin and obscenity. In the midst of primordial paradise it has created gulag and concentration camp; it has carved swastikas on the walls. We live in a world where the heartless and strong grind the face of the helpless poor, hanging tears on the cheeks of children, a world of disease and pain, of betrayal and despair, of birth defect and sudden premature death. We have come to know thalidomide and cancer.

We come into life without our consent and depart from it against our will. Historians testify that life is short and brutish and that civilization is but a fragile veneer painted over it for a time. We are born into a vale of tears and the days of our strength and youth are but few. In this life we walk and die under a shadow.

But there is good news—the good news that this shadow will one day depart and the whole world will one day be filled with the glory and the light of the Lord as the waters cover the sea. Even now the light has begun to dawn. It touched the earth first at Bethlehem and then began to spread to wherever the divine Name of Jesus is loved and worshipped.

Because of Jesus we have a way through the darkness of this age, an entrance into the true land of the living. God indeed brings the night of death, but as fast as He brings it, He brings eternal day. Stepping through the dark door of death brings us into a sunlit land, into a day that knows no evening, into the eternal Pascha, into a place where all tears are wiped away and where joy shines eternally and triumphantly.

Knowing this to be true, it makes no sense to burn and rave at the close of day when the time has come for us to leave this land of shadows forever and step into the everlasting sunshine; it makes no sense to rage and rage against the passing of the darkness and the coming of the victorious light. What does make sense is for us to run to that light when the time for our passing finally arrives, to burst through the door into the arms of heaven. St. Paul knew this and wrote that he desired nothing more than to pass through that door; he wrote, “For me to die is gain…my desire is to depart and to be with Christ” (Philippians 1:21-23).

The night of death will come for us all but if one has served Christ in this age it will indeed be a good night. We should not rave and rage and burn when that night is finally upon us, nor go gently and reluctantly towards it, but boldly and triumphantly and with tears of joy.

That is why I now regard the poem by Dylan Thomas as strange—he rages and resists something which he should embrace. For a Christian, the moment of death is not annihilation, but homecoming. The light that the poet loves is not dying; it remains eternally and beckons the Christian to enter into it more fully, for it is the light of Christ. We should run through the door of death with eager feet for our Lord waits for us on the other side.