I have recently come across the teaching that Orthodox Christians should not pray for non-Orthodox. I cannot cite the details of who-where-when, so perhaps I am misunderstanding what is being said. But the concern to differentiate Orthodox from non-Orthodox in our intercessory prayers is real enough: I have been in one Orthodox Church where the list in the narthex on which one could write names to be prayed for in the Litany of Fervent Supplication has separate columns for Orthodox and non-Orthodox. I know of another church where some parishioners write down the names and then add “(non-Orthodox)” after them. What are we to make of this? Are there such requirements made on liturgical prayer?

Obviously there are differences between Orthodox and non-Orthodox Christians. If the latter showed up in church for Liturgy we would welcome them, but not commune them. But interceding for them in their absence is something else entirely. One asks: how does intercession for a non-Orthodox differ from intercession for an Orthodox? When in prayer we offer their names to God (who surely knows who is Orthodox and who is not) do we speak their names differently? Do we raise our voices and speak a little louder when reciting the names of the Orthodox? Or of the non-Orthodox? Do we smirk when praying for the non-Orthodox and offering their names? Do we slouch?

Presumably we do none of these things. Rather, we simply recite their names as we intercede for them, confident that God knows all about them and will answer our prayers as seems best to Him. Humility in prayer requires that we offer people to God and leave the rest with the Most High.

We see this in the liturgical prayers offered at the proskomedia (the pre-Liturgy preparation of the gifts of bread and wine, getting them ready for the Great Entrance), and in the Litany of Fervent Supplication. In those prayers, we pray not only for bishops, priests, and Orthodox laity, but for our secular rulers as well.

At the proskomedia, a particle is taken out of the prosphora and placed on the diskos, commemorating (in the words I was taught) “our land and its rulers” (the wording differs in different service books). In the Litany of Fervent Supplication, we are instructed to intercede for the head of State (in Canada, King Charles, in the U.S, “the President of our country”) as well as for “all civil authorities and for the armed forces”. These last people—the head of State, the civil authorities, and the armed forces—are not necessarily Orthodox, or even Christian. But we pray for them nonetheless, and do not remind God of the fact while praying for them. Presumably the Most High knows that King Charles and Joe Biden are not Orthodox, without any help from us. What He will do with our intercessions and how He will deal with them is, to be blunt, none of our business.

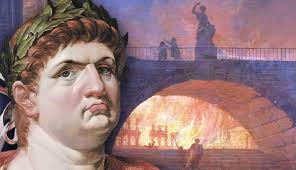

This concern to intercede for the head of State and for our rulers goes back to the apostles. In 1 Timothy 2:1f, St. Paul writes “I urge that supplications, prayers, intercessions and thanksgivings be made for all men, for kings and all who are in high positions”. St. Peter writes more or less same thing in 1 Peter 2:17, where he tells us to “Honour all men. Love the brotherhood. Fear God. Honor the emperor.” Presumably this honouring of the emperor included prayer for him, as Paul instructed. And who was this emperor of whom Peter and Paul wrote? It was the emperor Nero.

That’s right: Christians were instructed to honour and pray for Nero, a very bad man indeed, and the first and notorious Imperial persecutor of the Christians. You could hardly get more secular or pagan than Nero, yet we were instructed to pray for him nonetheless.

This instruction points to the Church’s universality of concern, and its generosity of heart. The Church still differentiated between Christian and non-Christian, and between Orthodox and heretic, but it offered them all to God in prayer as it interceded for the world. Indeed, one writer (Dix?) observed that when looking at the Church’s prayers in the pre-Nicene days of persecution and the post-Nicene days of Imperial favour, one could not detect any real change of attitude to the secular authorities or to the world at large. In both periods the Church prayed that God might bless the world and its secular ruler so that we could live in peace and tranquillity.

During times of increased secular hostility and stress (like our present time) the temptation is always to pull up the drawbridge, fill the castle moat, erect higher barricades and hide behind them—in other words, to become fearful of secular contamination and threat. The secular World is and has always been a place wherein one can suffer contamination, but we have been promised protection from it. That is partly what the Lord meant when He said that we will have authority to tread upon serpents and scorpions and nothing would hurt us, and that we would pick up serpents and drink any deadly thing without suffering harm (Luke 10:19, Mark 16:18).

That is, we will be able to walk safely through the world and still preserve our purity of heart. Of course our vigilance is needed for this, as well as the Lord’s protection. But we need not shrink from interaction with the world, nor cower behind the drawbridge or the barricade.

That is what cults do. Indeed, such fear of the contaminating World is almost what constitutes a group as a cult. One thinks of the Jehovah’s Witnesses and such groups as the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints, with their isolated compound ranch. Such groups live by spreading fear among their members that the World outside the cult is contaminating and dangerous, and that salvation consists in avoiding the contamination by remaining safely behind the boundaries erected by the cult.

In this culty mindset, people are no longer just people—i.e. individuals whom God made and for whom Christ died. They are representatives of the dangerous land outside the boundaries separating the cult from the world of the damned and the doomed. For such people, John Doe is no longer “John”, but “John (non-member of our group)”—and therefore potentially a source of contamination. Pray for him if you like, but stay clear.

It was always otherwise in the Church, for the Church is not a cult, but the Kingdom of God on earth, the Body of the Saviour who died for all and who continues through us to reach out to all. We pray for everyone with a kind of cheerful disregard for their present status, commending them to the love of God. On the cross our Lord stretched wide His arms to embrace the world, and we must do the same. God loves the world, and calls us to offer it back to Him in our prayers.