I would like to invite you to come with me on a journey of imagination that may help us to understand what it was like to live in “Bible times”. To make this journey you will need to leave behind absolutely everything you know about geography and science.

That is, forget that we now know that the earth is a round sphere moving throughout space and going around a stationary sun. We are familiar with the map of the world and therefore know that the world consists of several continents of varying shapes, each one separated by large bodies of water called oceans. We know that if one somehow travels straight up then the air we that breathe grows thinner and thinner and eventually gives out so that we find ourselves in “outer space”. We must forget this too.

We must also forget other things. Outer space is unthinkably vast and populated by stars and planets arranged in galaxies. God does not physically live anywhere “up there” in outer space (as Soviet cosmonauts confirmed in a bit of idiotic propaganda). After the breathable air gives out, there is nothing really there that has anything to do with us. (The moon-landing, though impressive, and inspiring for SF fans who want to boldly go where no man has gone before, had no immediate practical value in itself: we didn’t need the moon rocks; we have plenty of rocks down here.)

Having temporarily forgotten all this, let us return to the geographic and scientific world found in the Biblical text, a world shared by Israel’s neighbours. Our first lesson about this conceptual world is found in the second verse of the Bible: “The earth was desolate and useless [Hebrew tohu and bohu; compare the use of the word bohu in Deuteronomy 32:10 and Job 12:24] and darkness was over the face of the deep and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters”.

Please note, forgetting all your science lessons— and possibly most of your Sunday School lessons as well— before God began to create on the first day and said, “Let there be light!” everything was sea in the dark. The Hebrew words rendered “the deep” and “the waters” leave no room for doubt. This was the view of the pre-creation state shared by Israel’s neighbours too. Thus, for example, the Enuma Elish: “A holy house, a house of the gods in a holy place, had not been made, a reed had not come forth, a tree had not been created, a brick had not been laid…all the lands were sea”.

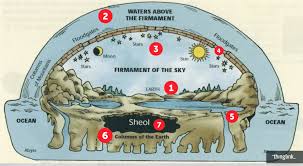

The remainder of Genesis 1 gives further details about what God by His Spirit did with that water (see inset image above embodying the ancient cosmological picture). Specifically, He created a divider, a firmament, separating the waters down here from the waters up there. The Hebrew word for the separator is raqia’, from the verb raqa, “to hammer out”. This was a solid barrier keeping the waters above safely up there so they could not fall down and drown us all. Job 37:18 uses a different word to describe it, but its nature is the same: the sky is “hard as a molten mirror”. So, there are waters down here under the sky and waters up there, “above the sky” (Genesis 1:7). Then God gathered all the waters below the sky into one place so that dry land appeared (Genesis 1:9). It was those “waters above the sky” that David later exhorted to praise the Lord (Psalm 148:4).

Let’s recap: in the Genesis story the world consists of a sea above the sky and a sea down here below the sky. (One wonders if the ancients perhaps concluded that the sky was blue for the same reason that the ocean was blue—viz. because there was an ocean up there.) There were, they reasoned, windows in the sky through which some of the sea water fell into the clouds which then watered the earth when it rained. (We find those windows mentioned in Genesis 7:11 and 8:2.) If the windows were left open for too long, the waters of the celestial sea fell to earth and flooded everything. This happened in the days of Noah.

Here is where imagination comes into its own. What, I ask, must it have been like to live your whole life under the sea, beneath the waters of a celestial ocean which could (and, they felt, did) at one time drown everyone on earth? Such a thought taxes our modern imaginations because we know that we are not in fact living under a celestial sea and that there is therefore no danger of it all coming down to drown us. But that is not how the ancient Israelites felt. They felt that they were living under a sea.

And here, I suggest, is the pay-off for such an act of imagination: the ancient Israelites didn’t live in constant fear, anxiety, and apprehension because they knew that their God Yahweh controlled all. His heavenly temple was enthroned above those heavenly waters; “He laid the beams of His upper chambers in the waters” (Psalm 104:3). Those waters above the sky obeyed and praised Him along with His angels and the sun and moon and stars of light (Psalm 148:1-4). Given Yahweh’s power, everyone was safe.

We can scarcely imagine now how the ancients felt about the fragility of life— and especially how they felt about the sea. We like the sea— sea-side property is valued and we delight in a day at the beach. John Masefield famously said in his poem Sea Fever, “I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky, and all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by… I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied”, but Masefield was not an ancient Israelite—or an ancient anything. He liked the sea; the ancients didn’t.

The ancients regarded the sea as menacing, an ever-present threat of death, a vestige of the primordial chaos. The pagan god Marduk slew the sea; the pagan god Baal also warred against the sea, which was paired with death in Baal mythology. As one scholar said, “In the Near East, life was often experienced as a desperate struggle against the forces of chaos, darkness, and mortality. Civilization, order, and creativity could be achieved only against great odds” (thus Karen Armstrong in her book Jerusalem). Ancient people did not like the sea; it was an image of chaos, ever threatening to overwhelm. Yahweh, however, protects us by saying to the sea “This far you may come but no farther and here your proud waves must stop!” (Job 38:11).

Today we no longer share the ancient cosmology with its belief in a celestial ocean above the sky, just as we no longer believe that the sun moves across the sky around a stationary earth. We can recognize that the Bible was not given to teach astronomy, meteorology, or any of the other sciences but rather to reveal God’s love and plan for us. Like the parts of the Bible which refer to a moving sun (e.g. Psalm 19, Joshua 10), the cosmology in Genesis represents God’s condescension to us, His acceptance of our human understanding and His using it to teach us the lessons we needed to learn.

The ancients believed that we all lived under a sea and that the world was constantly threatened by chaos. Despite the error in cosmological details, they were not wrong. For we know that our world is at the mercy of forces we cannot control— forces like hurricane and tsunami and pestilence and drought and famine. We are even at the mercy of astronomical precision, the distance of our proximity to the sun— if we were further away from the sun we would all freeze to death; if we were closer to the sun, we would all burn. Life on earth is dependent upon our being exactly where we are vis-à-vis the sun. Existence is lived on a knife-edge.

The opening story in Genesis tells us that we don’t need to be afraid, that we can live and die without fear. Whether we live under the sea or live under the threat of nuclear annihilation or live under the threat of economic collapse or imposed tyranny, we don’t need to be afraid. Our God is in control. Even our mortality— not the threat of death but the certainty of it— need not make us tremble, for God is with us. His throne might not be an actual chair in a palace built above a celestial sea but it is secure nonetheless and from His throne He rules over all creation. We can sleep at night peacefully and secure, knowing that we all sleep under the shelter of His wings.